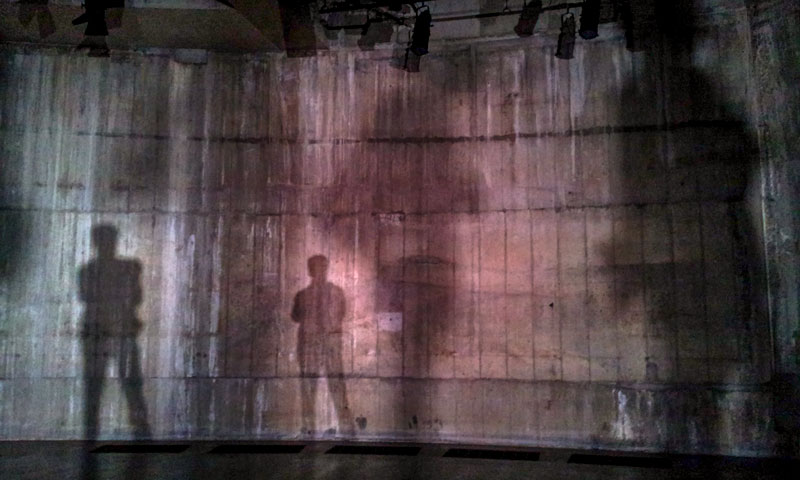

Clergy-perpetrated child abuse can have a dramatic effect on children’s faith, family relationships and how they view the world.

Clergy-perpetrated child abuse can have a dramatic effect on children’s faith, family relationships and how they view the world.

Christian churches in Australia and around the world have faced a raft of allegations of clergy-perpetrated child sexual abuse as well as accusations of inadequate efforts to bring perpetrators to justice.

Encouraged by an increased focus on the issue as well as several inquiries, including the ongoing Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, an increasing number of Australian victims are coming forward to tell their stories and seek help.

So what separates clergy-perpetrated abuse from other types of child abuse?

Crisis of faith

In contrast with the large body of evidence examining the prevalence and health consequences of child sexual abuse occurring in the general community, very little research has looked specifically at clergy-perpetrated abuse.

Some studies have identified an additional theological and spiritual dimension that sets clergy-perpetrated abuse apart from other forms of child abuse. This type of abuse has been described as “a unique betrayal” and the “ultimate deception” by a significantly older abuser who transgresses their duty of care and abuses their power.

One victim described the effect of their abuse to advocacy group Broken Rites Australia as:

“Shocking, bewildering and devastating. I was taught to unconditionally trust the church and clergy. The actions of [the priest] broke this trust. I had nowhere to go. I was too embarrassed to tell my mother and I did not trust the church. This led to inner conflict, confusion, fear, trauma and anxiety. I lost my faith, my respect for the church, my self-confidence and esteem”.

Another victim remarked to an American study:

“I mean, if you and I couldn’t trust our parish priest; excuse me. Point out someone to me that I can. This is the one guy who came with all the credentials that was certified as trustworthy and we couldn’t trust him”.

Unsurprisingly, many people identify clergy-perpetrated abuse as marking the end of any ability to have any faith in their faith. Some go on to look elsewhere for spiritual meaning in their lives, but very often it’s outside the religion they started in.

Double betrayal

In addition to betrayal by the religious institution, many victims feel betrayed by family members who struggle to understand what has happened. Compare a case of clergy-perpetrated abuse with a case of child abuse where a member of the clergy is not the perpetrator. If a child was abused by a stranger walking home from school, chances are they would tell their parents straight away. Immediate social and psychological support would be provided, and the school would be briefed about the child’s needs.

This contrasts dramatically with the likely sequence of events when a child is abused by a member of the clergy. In this circumstance, the child may not tell their parents or anyone else about the abuse – studies have found many victims take an average of 23 or 24 years to disclose their abuse.

If the child does disclose the abuse, the parents may not believe the child because the revelation tears at the fabric of their religious identity and they may struggle to comprehend that a member of the clergy could harm their vulnerable child so profoundly. The situation is further complicated when children attend a school of the same faith.

As a result, the child may believe there’s something wrong with them and feel deeply stigmatised.

If children feel blamed, judged or disbelieved, it can result in very severe psychological consequences and can often delay any further attempt at disclosure or seeking help for many years. American research has identified post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a common psychological effect of clergy-perpetrated child abuse. Victims are also more likely to be affected by self-harming and suicidal behaviours, alcohol misuse, depression and anxiety.

A recurrent theme in Australian victims’ accounts is how their parents’ religious beliefs and trust and reverence for members of the clergy meant that they could not conceive of the possibility that priests could sexually abuse their children and betray their own vows. Yet there is ample evidence that this trust and reverence was sadly misplaced and the same caution that would be applied to other members of society needs to be applied to members of the clergy.

Family relationships

Along with the psychological effects of a ‘double betrayal’, many victims struggle to maintain relationships with their parents and other family members into adulthood. Children have a natural belief that their parents will protect them and keep them safe from danger and harm, and if their parents don’t fulfil that need, children can feel desperately alone with their pain.

Even if families can get past this betrayal, it’s unlikely that they will ever return to a sense of pre-abuse ‘normal’ because children have an altered world view and sense of self. For many victims, going back to how they were feels unlikely because they’ve been broken and rebuilding will result in something different to how they started.

It’s important for families to be aware that it’s not simply the child’s traumatic symptoms that require attention. There’s going to be an existential crisis of sorts for the child because of the breakdown of their values to do with justice and trust. Because their faith, which is often a source of great meaning and comfort, has been shattered and there are corresponding dramatic changes to how children see themselves, the way they respond and adapt to stressful events and understand the world will have been largely destroyed and needs to be rebuilt.

By Professor Jill Astbury MAPS

Honorary Professor, Psychology Department, Victoria University

If you or anyone you know need assistance please contact:

- Lifelife on 13 11 14

- Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800

- MensLine Australia on 1300 789 978

- Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467

- Beyond Blue on 1300 22 46 36

Original Psychlopaedia Article

Original Psychlopaedia Article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

by Marco Bianchetti on Unsplash