The gut-brain axis opens a whole new way to influence mental health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 280 million people worldwide suffer from depression,1 with rates tripling since early 2020. 2 The Anxiety & Depression Association of America adds to these grim statistics, reporting that around 40 million adults suffer from significant anxiety3 — though it is widely believed that such statistics are grossly underreported. 4

The standard-of-care treatment for anxiety and depression includes a combination of medications and psychotherapy.5 But while research has made progress in refining diagnostic testing and developing prescription drugs, the rates of depression and anxiety continue to rise, suggesting that the dominant approach to psychiatric healthcare is insufficient.

WHO estimates that 80% of people are looking for alternative options for their mental health.6 Many of those affected have turned to the research focused on the gut-brain axis for answers.

In the early 2000s, psychiatrist James Greenblatt, M.D., began teaching about the “second brain.” He contended that all humans have trillions of mood-modulating microbes and networks of neurons populating their guts. He even argues that “psychiatric woes can be solved by targeting the digestive system.”7

In the 2017 book, The Psychobiotic Revolution, author and journalist Scott Anderson teamed up with medical researchers John F. Cryan, Ph.D., and Ted Dinan, M.D., Ph.D., from the APC Microbiome Institute at the University of Cork, Ireland. Corroborating the claims made by Dr. Greenblatt, the authors emphasize the relationship between the gut and the brain, writing: “Some of your deepest feelings, from your greatest joys to your darkest angst, turn out to be related to the bacteria in your gut.” 8

The Microbiome & Microbiota

There are over 100 trillion microorganisms living in each person’s body, collectively referred to as the microbiota.8 The microbiota is a component of what researchers call the microbiome, which includes the microbiota, bacterial genetic material, functional microbial activities, and the ever-changing ecosystems of other cells, viruses, and bacteria.9 In fact, the microbiome refers to the collection of microbes inhabiting all the tissues of the body, including the skin, many of which provide essential functions.

Existing research indicates that the architecture of a person's gut microbiome is largely hereditary. Each individual’s microbiota has been passed down from their ancestors and is as unique as their fingerprint.8 A number of gut microbes, either directly or through substances they release, influence the functioning of the nervous system and affect states of mind and behaviour; they have been dubbed psychobiotics. 10

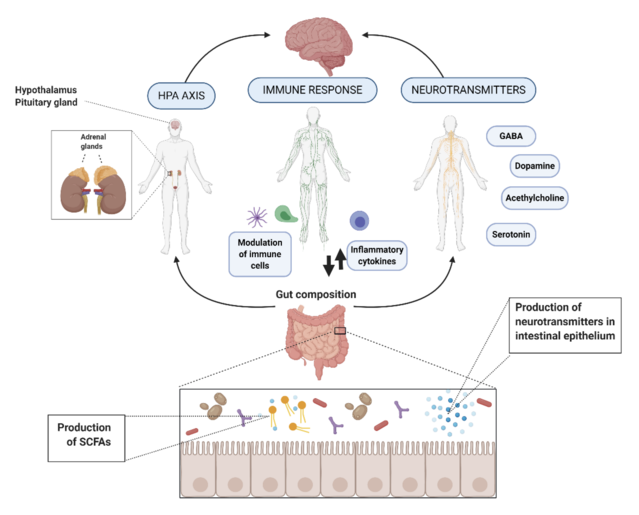

The mechanisms by which microbes are able to modify mood and cognition are complex and varied depending on the characteristics of each unique microbial strain. For example, specific strains of Lactobacillus reuteri can release the mood stabilizing neurotransmitter serotonin—increases of which are associated with reduced depression. Strains of Lactobacillus plantarum produce GABA, a neurotransmitter known for its anti-anxiety effects.

And different species and strains of Bifidobacterium are able to digest fiber to make butyrate, a substance chemically classified as a short-chain fatty-acid (SCFA). Butyrate feeds and repairs the cells of the intestinal tract, tightening the junctions between them to reduce the potential for bacterial and toxin leakage into the bloodstream (leaky gut) and subsequent inflammation in the body and brain.8 As research continues, it’s likely that new mechanisms and unique psychobiotics will be identified.

A Communications Superhighway: The Gut Brain Axis

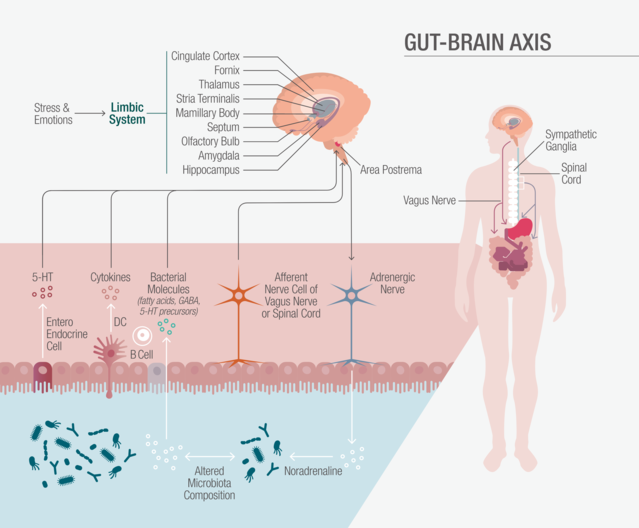

The gut-brain axis is the bidirectional communication pathway between the gut and the brain.11

While the mechanisms of communication are extremely complex and are still being studied, Cryan and Dinan suggest that the gut-brain axis is comprised of five primary systems which communicate via three main channels.1

The five physiological systems of the gut-brain axis include:

(1) The gut microbiome

(2) The central nervous system (CNS): including both the brain and spinal cord

(3) The autonomic nervous system (ANS), the nervous system responsible for automatic functions including heartbeat and breathing, which is regulated, in part, by the vagus nerve

(4) The enteric nervous system (ENS), the nervous system of the gut

(5) The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the hormonal feedback system responsible for the stress response.

(1) The nervous system, which relays information in the form of neurotransmitters to and throughout the brain via the vagus nerve

(2) The immune system, which communicates via inflammatory cells, called cytokines, to activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis)

(3) The endocrine system, which involves glandular release of hormone signals throughout the body,—for example, cortisol released by the adrenal gland

The vast majority of the communications begins in the gut, and therefore the functioning of the brain is heavily influenced by the health of the gut and the state of the microbiome.

Closing Remarks

The Mood, Mind & Microbes blog aims to keep you apprised of the latest advancements in gut-brain research from notable academic institutions, as they relate to mood and mental health. We will also include clinical perspectives on approaches to achieving better mental wellness by addressing gut health. Our ultimate goal is to help support a more holistic and integrative approach to addressing mind-body balance.

Author

Nicole Cain, ND, M.A., is a naturopathic physician, with a master's in clinical psychology. Her expertise is in integrative mental health, complex trauma, and mood disorders. Dr. Cain practices in Scottsdale, AZ and is writing a book about anxiety.

References

Depression. (2021, September 13). World Health Organization.

McKoy, J. (2021, October 14). Depression Rates in US Tripled When the Pandemic First Hit—Now, They’re Even Worse. Boston University.

Facts & Statistics | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. (2022). The Anxiety & Depression Association of America.

Washington State Department of Health. (2021, December). Week of December 13, 2021 COVID-19 Behavioral Health Impact Situation Report. Washington State Department of Health’s Behavioral Health Epidemiology Team.

The American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Clinical Practice Guidelines | psychiatry.org. Web Starter Kit.

Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Overview. (2016, December 12). WebMD.

Greenblatt, J., MD. (2020, September 16). The Verge.

(1) Anderson, S. C., Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2017). The Psychobiotic Revolution. National Geographic.

Berg, G., Rybakova, D., Fischer, D., Cernava, T., Vergès, M. C. C., Charles, T., Chen, X., Cocolin, L., Eversole, K., Corral, G. H., Kazou, M., Kinkel, L., Lange, L., Lima, N., Loy, A., Macklin, J. A., Maguin, E., Mauchline, T., McClure, R., . . . Schloter, M. (2020). Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome, 8(1).

Cryan, J. F., O’Riordan, K. J., Cowan, C. S. M., Sandhu, K. V., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Boehme, M., Codagnone, M. G., Cussotto, S., Fulling, C., Golubeva, A. V., Guzzetta, K. E., Jaggar, M., Long-Smith, C. M., Lyte, J. M., Martin, J. A., Molinero-Perez, A., Moloney, G., Morelli, E., Morillas, E., . . . Dinan, T. G. (2019). The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiological Reviews, 99(4), 1877–2013.

(1) Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of gastroenterology, 28(2), 203–209.