The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good

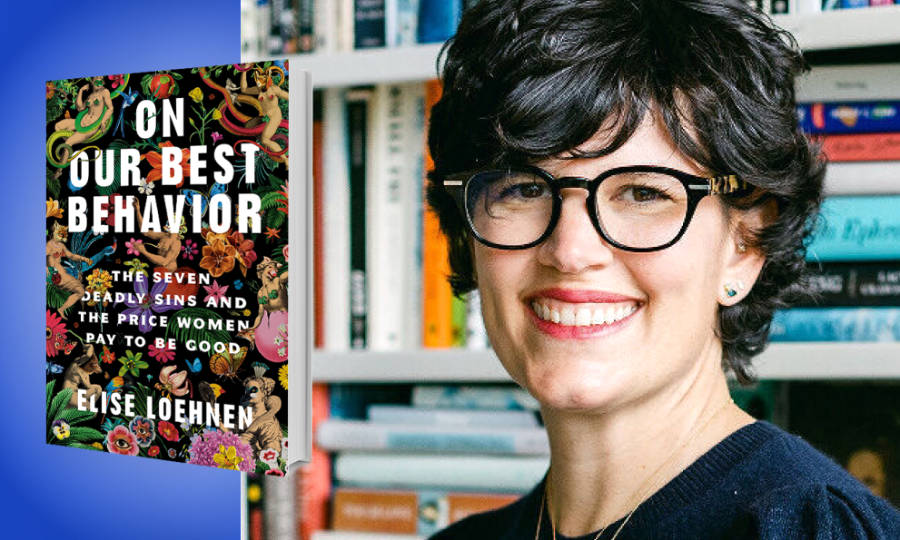

Elise Loehnen is the host of the podcast, Pulling the Thread. She has co-written twelve books, five of which were New York Times bestsellers. She was the chief content officer of goop, and she co-hosted The goop Podcast and The goop Lab on Netflix. Previously, she was the editorial projects director of Condé Nast Traveler.

Below, Elise shares 5 key insights from her new book, On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good.

Listen to the audio version—read by Elise herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Women are programmed for goodness, while men are programmed for power.

These qualities are not who we inherently are, but who we are told to be—in short, roles we are expected to perform. Anthropologist Ashley Montagu talks about this as first and second nature. First nature is who we biologically are, at our core. Second nature, according to Montagu, is the way society informs this biology and how it shapes our beliefs about who we are. Our second nature is story—a very powerful story, a story that we whisper into each other’s ears. In this way, culture becomes contagious and largely invisible. In fact, biology and culture are so conjoined in humans, it’s impossible to tease them apart: Does nature drive culture or the reverse?

In this way, goodness has become a prison for women, particularly because goodness in our society is mediated by an external judge. We are chased by feelings of not-good-enough-ness. We do not allow emotions that we consider “bad” to emerge so we can diagnose, process, and use them.

The punch card for goodness for women is so obvious, it’s invisible. It’s the Seven Deadly Sins: sloth, envy, pride, greed, gluttony, lust, anger. These are the voices in our hides, chiding us to do more, eat less, stay small and quiet. An instinct to deny these essential human qualities lives in all of us, regardless of whether we were raised adjacent or in any faith. These qualities are cultural at this point, not religious. In fact, they are actually Bible FanFic—they weren’t in the Bible, they emerged out of the Egyptian Desert at the same time that the New Testament was canonized.

2. Women are conditioned to subjugate our wants to other peoples’ needs: The wanting of women must be given a voice.

In an interview with therapist Lori Gottlieb, author of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone, she offered a critical insight—she tells her clients to pay attention to their envy because it tells them what they want. For women, though, envy feels so bad when we want so desperately to be good, that we miss its signal. When envy comes up in our bodies, our immediate instinct is to suppress and repress it, rather than letting it emerge so we can diagnose it and use it to understand what it’s trying to tell us about what we really want.

“We find reasons to criticize and condemn her when we should understand that this woman in question is full of information that we need.”

Undiagnosed envy often comes out sideways too. We are conditioned to judge the object of our envy, whoever is making us feel uncomfortable. We say things like, “I just don’t like her,” or “Who does she think she is?” Or, “She only has that because of this reason, or that.” We find reasons to criticize and condemn her when we should understand that this woman in question is full of information that we need. She is pushing on a dream we have for ourselves, and it is our job to use that as a compass for what we want in our lives.

3. Our fear of sloth—i.e. not doing enough, for everyone, in all spheres of life—is killing us.

The pressure on women to be good at everything—to be good mothers, for one, along with conscientious and caring colleagues and leaders—only seems to ratchet up. In the fallacious quest for “work-life balance,” we seem to be trying to equalize our lives by continuing to add more to each side, and on and on. This lives deep in our psychology, meaning that the unburdening can’t happen solely through systemic changes, but will also require deep, personal work to do less. We must do less so we can be more to ourselves.

Our busy-ness is also ratcheting up because it’s one of the primary numbing mechanisms to keep all of our bad feelings at bay. Rather than allowing our anger to come up, for example, we can work through it, literally, or distract ourselves with endless to-do lists rather than address our rage.

4. Telling women that we must bridge an achievement gap, or “be more confident” is a moral crime.

Women don’t lack confidence. Women are exceptionally confident; we just know to lead with competence instead. We know better than to show our confidence. In fact, we spend a lot of time cushioning our confidence to make ourselves more palatable, more likable. All of the social science supports the fact that men and women alike are hard on women “who think they’re all that.”

“We spend a lot of time cushioning our confidence to make ourselves more palatable, more likable.”

Look no further than what we do to women who dare to be seen. They all seem to follow the same trajectory. We applaud them on the way up, and then when they hit a tipping point, we celebrate as they’re shot out of the sky. This happens to celebrities, musicians, business leaders, and athletes—it’s a playbook for women we deem prideful. Normal, civilian women can try to believe that what we’ve done to these highly-visible women has nothing to do with the rest of us, but this pattern recognition is buried deep into our consciousness. We know attention is dangerous, and we have to start vocally interrupting this pattern to change it.

5. Fear and avoidance of sadness have lodged in the minds of men.

The primary symptom of this severing from emotion is toxic masculinity. It’s represented by a fear of death, a fear of the cycles of life, and a fear of the loss of power. It’s countered by a desire to control the planet, control people, and dictate a growth curve to go up and to the right.

We are a culture drenched in unresolved grief. Women must let their wanting come up, and men must let their sadness come up. Therapist Terrence Real, who primarily works with couples and men, explains that while overt depression is more likely to be diagnosed in women, when you add up rates of overt depression, personality disorders, and addiction in men, the rates equalize: Men are far more likely to take their own lives. Men are more likely to suffer deaths from despair.

We often talk about patriarchy and its effects on women and marginalized people. Yes, those are its primary targets, but patriarchy is also killing men. Wounded boys become wounded boys. These are the agents who are wreaking havoc on all of us. Bringing men in contact with their sadness might offer relief to everyone. Through awakening the sadness in men, we can look to rebalance society and move toward a more equitable future.

Listen to the audio version—read by Elise herself—in the Next Big Idea App.